The European Romantic Movement gripped culture, through art, literature, music and political belief, this ideology stood as a stark bulwark against the industrialisation and reckless scientific advancement of the Enlightenment in the late 18th Century. The Renaissance period seemed to light a spark that led to fantastic improvements in our understanding of nature, science and ourselves as a whole, championing Protagoras’ philosophy of “Man as the measure of all things”. At a most basic level, Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’[1], a prime example of Gothic-Romanticism highlights the maltreatment of the ‘other’- women, the poor, the disfigured, whilst also highlighting the utter disrespect in conquering and transgressing nature. This leads me to my reasoning of creating the contemporary landscape. In our modern society, we have cast aside ‘Man’ and the human experience, digitising and quantifying every part of our lives with science and reason. There is no longer magic, there is no longer unknown and there is no longer excitement. We conquer nature by destroying our world, and we transgress our own humanity by making machines in the image of the human mind. I believe that my reaction to modern society is a contemporary variation of the Romantics’ rejection of their own society and through the landscape I wish to transport the viewer into a place where this wonder and magic still exists, I want people to experience the raw, undeniable power of the world around us which we seem to have lost.

During the Renaissance there were certainly ‘Romantic’ ideologies that were persecuted. The scholars, Paracelsus and Agrippa were believers that man may be the measure of all things, but man itself is measured by nature, chemistry and celestial bodies. Although many of their beliefs seem ridiculous now, there was a tremendous amount of truth, both spiritually and medically in what they discovered. Paracelsus was critical of his Renaissance education and stated that “a doctor must seek out old wives, gipsies, sorcerers, wandering tribes, old robbers, and such outlaws and take lessons from them. A doctor must be a traveller.”[2]. Paracelsus was one of the first scholars to focus and rely on the true human experience, traversing the globe to discover the forces of nature that control us. In the same respect, I create my art as a traveller, drawing from a breadth of lived human experiences to influence my work. Agrippa, similarly, believed in alchemy and that everything is constituted of the “seminal virtues of all things”[3], fire, water, wind and earth. Although seemingly ridiculous now, both scholars discovered wonderful things that helped many, and all while doing this focused on the divinity and magic in nature, that seem to be forgotten in contemporary society. Within my own work I have tried to echo the teachings of Agrippa. Is it not true that we are governed by the world around us? Our health is dictated by the minerals we eat and absorb, grown or reared from the soil. Is our mood not determined by the natural beings and circumstances around us? And physically, we are chemically altered by the phases of the moon and tides in menstrual cycles. Within my work I show this connectedness to space and capture these moments and elements within nature.

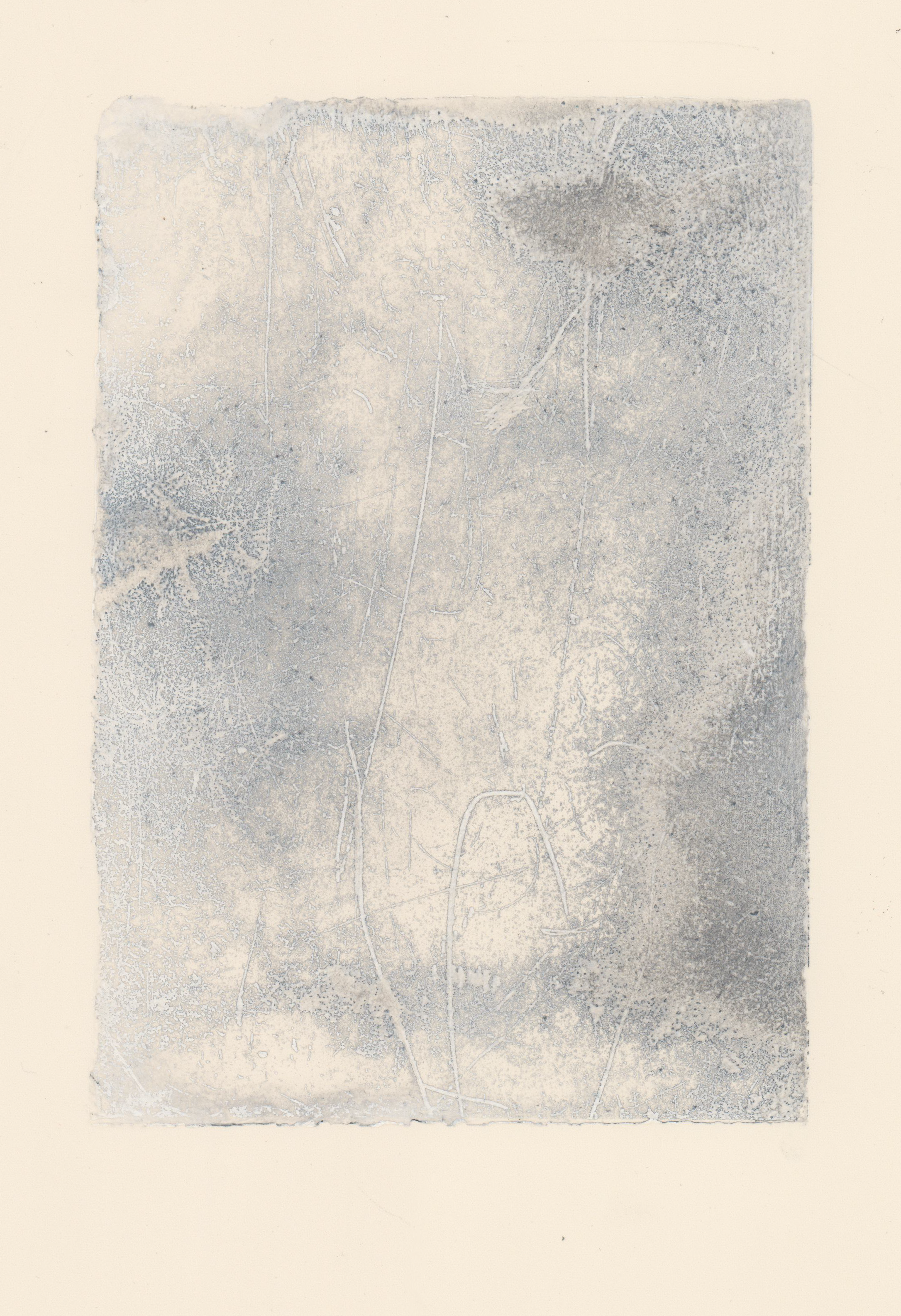

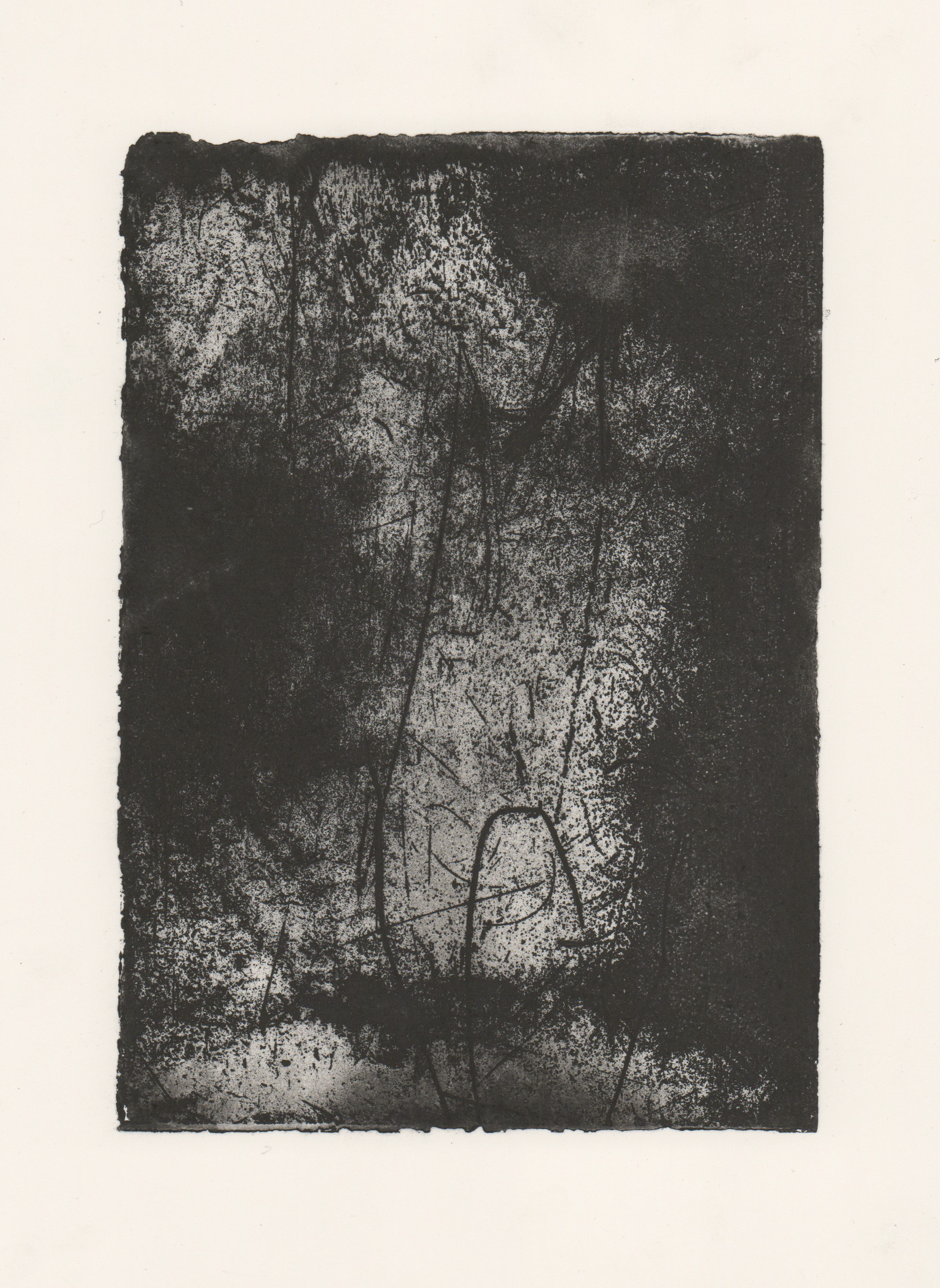

I bury my plates to expose them to the waterfall, or the sand in order to catch this natural magic at play. In my experimentations I have allowed metal plates to be warped by the immense power of the water, and then further processed them through more natural processes that are uncontrollable, through etching the plates deeply in acid to allow the touch of the water to become corporeal. In stilling these moments, I capture a visceral action of nature, and through the print matrix lying in situ for days, weeks or months, they too become a piece of nature, “For whatever has long stood with salt, becomes salt.”[4]

The Landscape itself is an interesting medium to portray the natural world, through a piece of landscape artwork, we view something stilled that is not fixed but in flux, Hanneke Grootenboer discusses this through her breakdown of Cornelius Claesz. Van Wieringen’s ‘Battle of Gibraltar’, a depiction of a Spanish flagship being destroyed by a smaller Dutch Galleon. Grootenboer suggests that through Van Wieringen’s apparent “[activation] of gravity”[5], he “stretches out the moment of explosion by spreading it out on canvas”. Van Wieringen captures a moment in flux, a moment of violent and visceral action becomes confusingly animate when stilled in paint. This notion is one that I reflect in my own work on nature and landscape, the capturing of a moment in flux, a remnant of intense power solidified on paper or metal or plaster.

It is of course difficult to create artwork about nature, without commenting on the state of the world at the moment. We live in a society that exploits and pillages the planet for its resources, a problem that is too ingrained within the mechanics of our culture for much of us at a personal level to change. My work offers an escapism and a reverence of the sanctity of nature that tackles change headfirst. How are we as a society expected to enact large changes in our lifestyles if we do not go out and experience what it is that we love and want to protect?

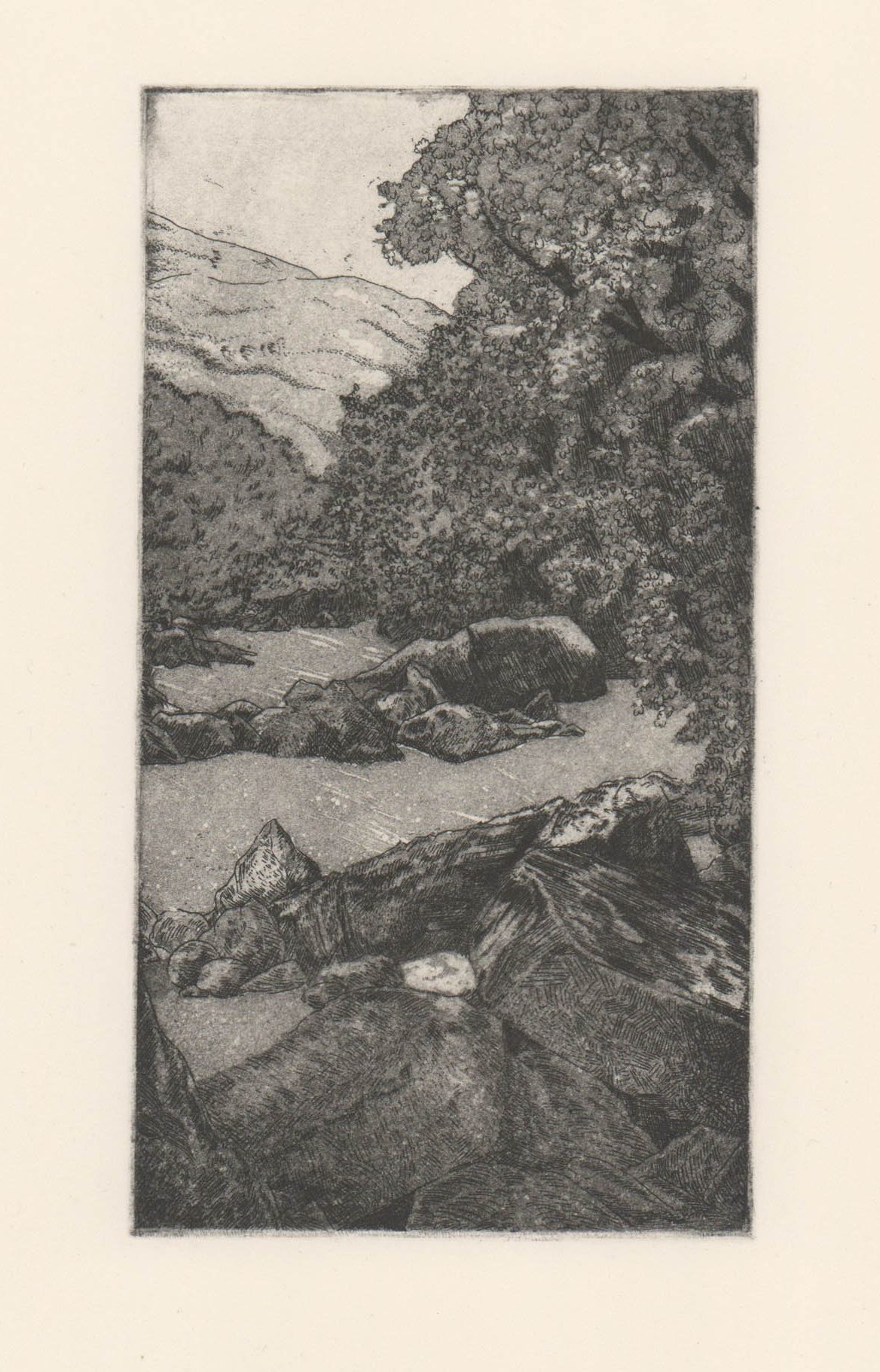

One issue that I have found in creating the ‘Landscape Sublime’ is making work about the experience of being in the places I love and respect, rather than creating ‘postcards’, as I did in the earlier part of the project, with my more traditional etchings. I feel a strong connection to J.M.W Turner in this respect, he paints with such emotive vigour that culminates in imperceptible strokes of paint, but from a distance, conjures these vast abstracted images of a boundless destroying sea, light and colour seem as primal elements in his work, as noted by Hazlitt; “The artist delights to go back to the first chaos of the world… All is without form and void.”[6]This cosmic sense of nature as a primordial and seminal force in life is something that as a contemporary society we seem to neglect.

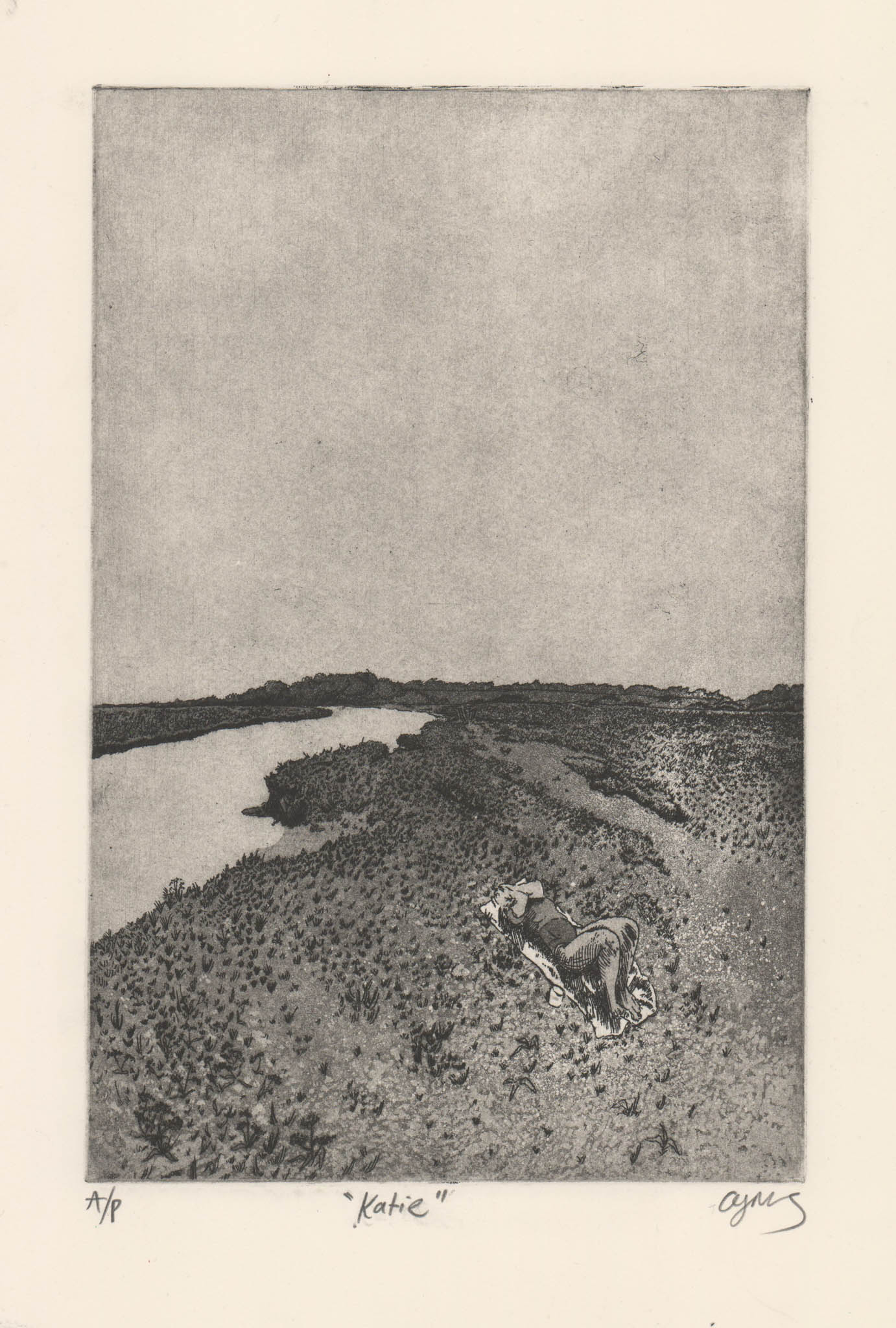

The places I choose to depict are massively important to me, the Chinese Geographer, Yi-Fu Tuan states that “place is a special kind of object. It is a concentration of value, though not a valued thing that can be handled or carried about easily; it is an object in which one can dwell”[7], this idea is something that I believe is prevalent in my work, I have chosen the landscapes of the North Norfolk coast, and the temperate rainforest of Healey Dell as they carry immense historical value that is linked to my heritage. On a broader scale, they also offer a sense of ‘Deep Time’, a phrase coined by John McPhee in his 1981 book, ‘Basin and Range’. In this book, McPhee offers a remarkable analogy that resonates with my own ideas about our cosmic insignificance, in the face of sacred and ancient nature; “Consider the Earth’s history as the old measure of the English yard, the distance from the king’s nose to the tip of his outstretched hand. One stroke of a nail file on his middle finger erases human history.”[8] This very sobering analogy is something that I have grappled with while creating my works, especially of the Stiffkey saltmarshes. The ancient, fossilised woodland that gave the village its name holds so much ancestral natural knowledge within it, it becomes unfathomable, this is where the sanctity in nature comes from for me.

[1] Shelley, M.W. (2018) ‘Frankenstein, or the modern Prometheus,’ in Amsterdam University Press eBooks, pp. 179–182.

[2] Hargrave, J.G. (2024) Paracelsus | Biography & Facts. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Paracelsus. (Accessed 24.01.25)

[3] Von Nettesheim, H.C.A., Tyson, D. and Freake, J. (1992, p.14) Three books of Occult philosophy.

[4] Von Nettesheim, H.C.A., Tyson, D. and Freake, J. (1992, p.40) Three books of Occult philosophy.

[5] Grootenboer, H. The University of Chicago Press. (2021, p.41) The Pensive Image: Art as a Form of Thinking.

[6] Finberg, A.J, R.A, Oxford Clarendon Press. (1961, p.241) The Life of J.M.W Turner.

[7] Tuan, Yi-fu, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press (1977, p.12) Space and Place : the Perspective of Experience

[8] Mcphee, J, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, (1981, p. 126) Basin and Range