I was lucky enough to see a few of Friedrich’s pieces in person in the National Gallery of Germany. Caspar David Friedrich was a draughtsman and landscape painter, a part of the German Romantic movement. His work is markedly anti-classical, depicting bleak and inhospitable imagined landscapes that forefront the often destructive and dangerous aspects of nature. Friedrich’s works such as his destroyed monastery series as well as the famous ‘Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog’, have a definite contemplative tone that places man as an observer, or an actor in this vast clockwork of nature. Friedrich’s use of figures really plant the viewer within the image. Immediately you yourself become a small piece of these vast and raw environments. The Romantic movement, especially in Germany acted as a resistance to uncaring scientific revolution and instead took a step back to forefront the individual human experience. We see a certain detachment to the contemporary world and Friedrich transports us to a space wherein nature rules and denies our transgressions against it. Friedrich’s works often contained religious elements, here overtly in the form of a ruined monastery, but in the case of his first acclaimed painting, ‘The Cross in the Mountains’, more subtly, with the natural world again being foregrounded. This work was criticised as it did not overtly depict a Biblical story like other classical Christian art would, and instead presents itself first as a landscape. Friedrich’s thoughts behind this piece echo my own feelings about the deistic elements of nature and landscape, the natural world feels perfectly cosmic and powerful enough to itself represent God. I don’t see the ‘Monastery Ruins in the Snow’ as a rejection or critique of religion, I instead see it as a point to reinforce the endurance of belief, with the monks still congregating despite the state of their sanctuary, and the all-encompassing power and will of nature. These works guide me to exploring tonality and mood within my work, throughout all of Friedrich’s pieces we feel an intense atmospheric quality, I want to transport people to the spaces I create and allow them to feel what I feel when I’m within the space.

Berlin Nationalgalerie-

I was really lucky to visit the German National Gallery in Berlin just before Christmas. I was really taken aback by the amount of gorgeous landscape on show. I was especially impressed by the beautiful selection of cloudscapes, I think that clouds are a really lovely way to build drama in a piece. I believe the inclusion of the heavens really deifies a work and connects it to some higher being. There is a wonder and an unknowing to clouds that is really just fantastic. I found that my favourite landscapes in the gallery were those where the clouds are foregrounded. The German Romantic movement does a great job of elevating nature, but also has this definite melancholic darkness to most of the pieces, these ideas are important to me and I want to reflect this darkness within my work, my monoprinted clouds were my first attempt at capturing this and I look forward to continue studying clouds.

Kip Gresham- The Legacy of a Master Printmaker- Eames Fine Art

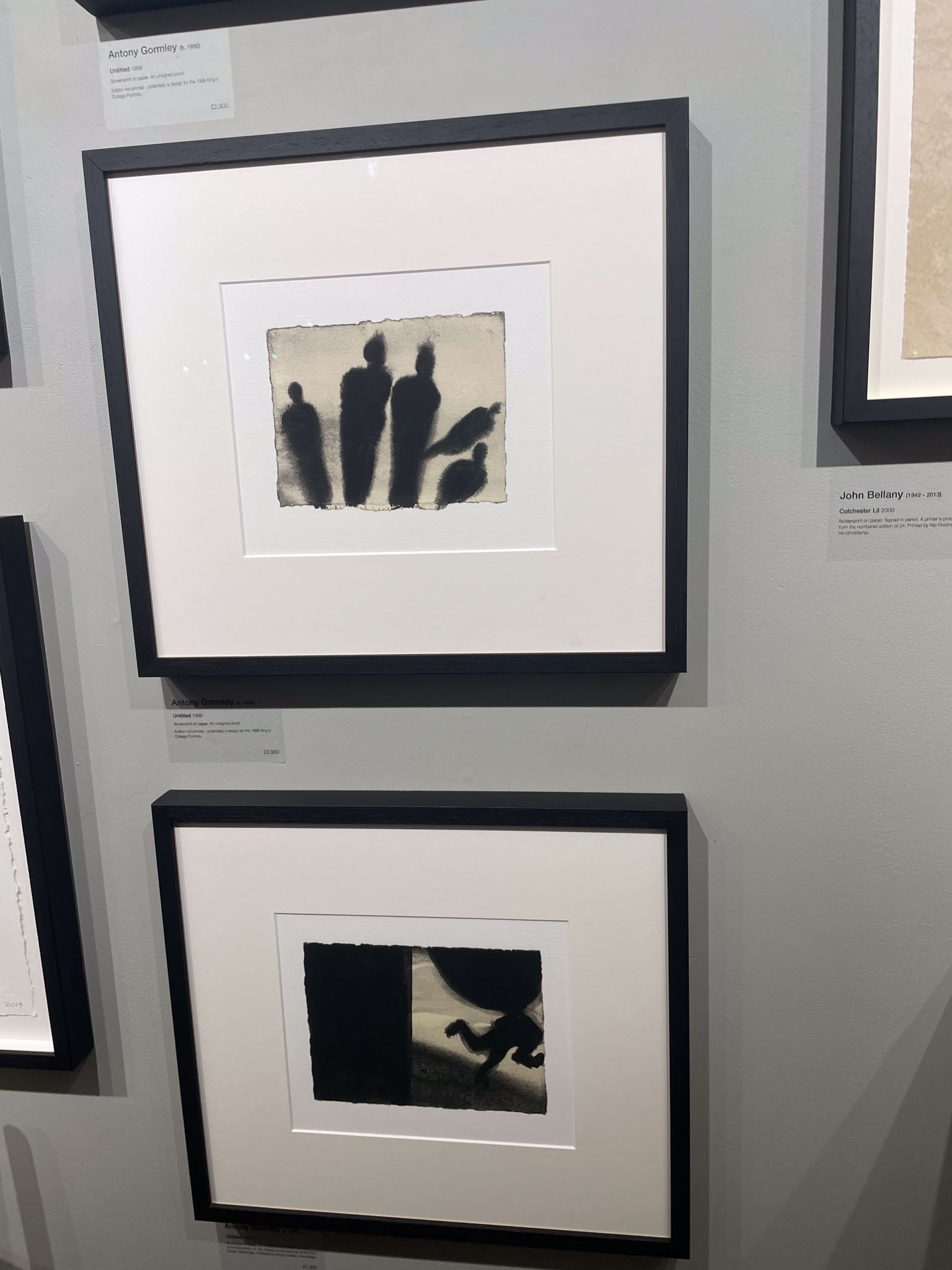

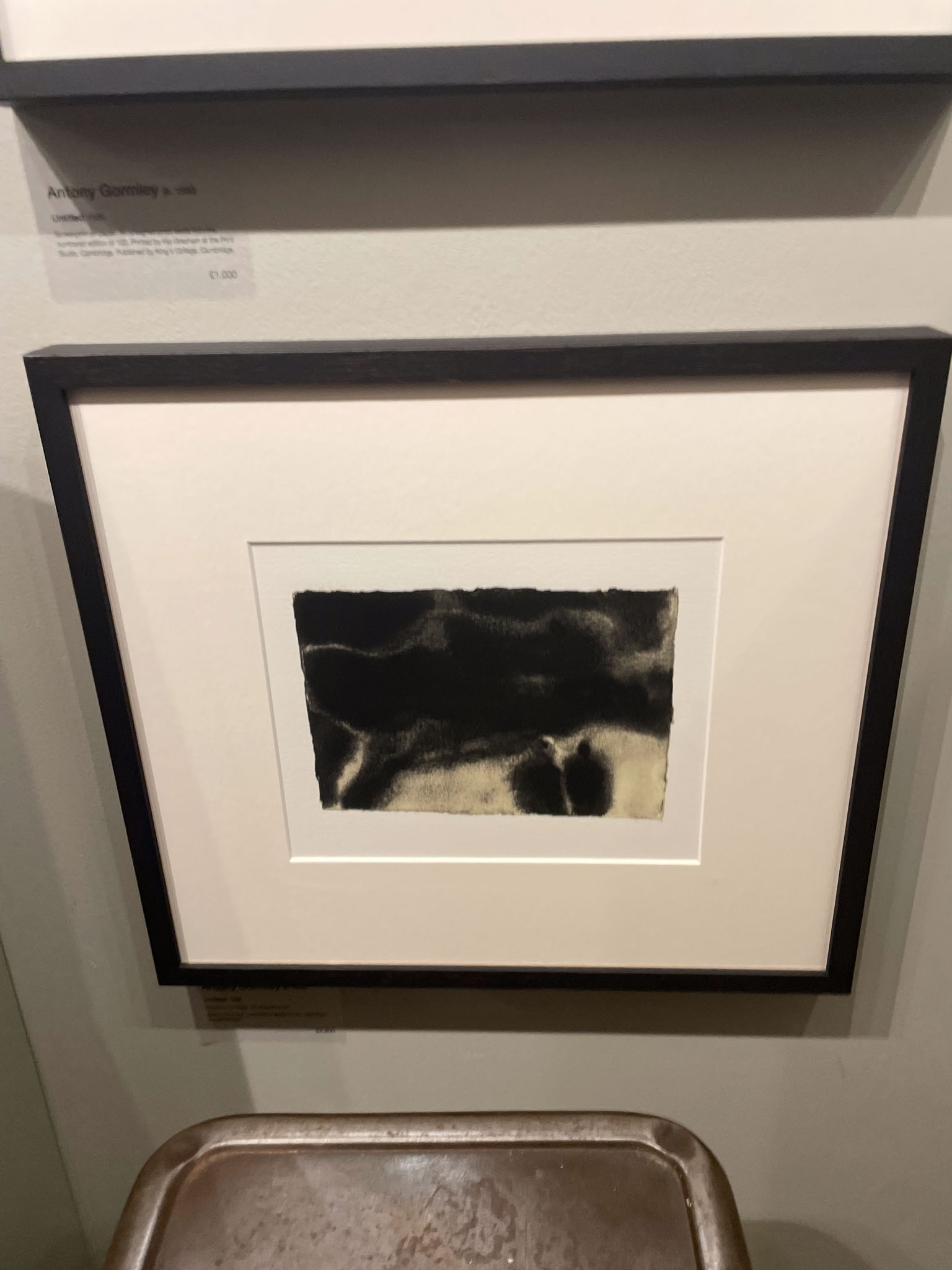

I was very lucky to have been invited to the Private View of this exhibition by my fellow student Sheila Woollam. I thought that the concept of the exhibition was really interesting, and it was amazing to see the private collection of a master printmaker, and what he deemed to be special enough to archive for himself. As a fellow printmaker, it became clear to me that the pieces Gresham had chosen to keep were not necessarily the most fantastic images, but an excellent display of skill as a printmaker and editioner. Most pieces in the collection were screen printed and technically were fantastic, even if I didn’t love the images themselves. Gresham expertly bends the boundaries of the medium of screen and creates amazingly subtle watercolour marks, or ink bleed, something I’d never seen done so subtly and delicately with the usually harsh and delineating medium of screen print. I did find some prints which I really loved, however:

Firstly, Tacita Dean’s beautiful work, ‘Foreign Policy’. Originally a chalk drawing on blackboard, expertly put into print by Gresham’s clearly very capable hands. I loved the boundless quality of the clouds, swirling in vortices. Dean originally created this series of cloud drawings in 2014 when a formation of clouds above Los Angeles resembled a ‘voluminous atomic cloud blooming’. This work echoes the uncertain, fragile and ever-changing political climate of the world through the transforming and ever-movable cloud formation. I found it interesting that this series of prints, created by Gresham were sent out to 15 UK diplomatic offices across the globe, with a print in Downing Street, as well as the original in the office of Sir Simon McDonald, Under-Secretary at the UK Foreign Office. I think that this really highlights the power of print as a multiple, the piece is a symbol of a gathering political storm cloud that is an ever present warning for our politicians negotiating and working with other countries. However, the production of the piece as print may undermine some of the thinking around the original; the original medium of chalk on blackboard is fragile and unfixed, the whole piece could easily be destroyed by a careless touch or an accidental wipe, however the medium of print fixes and solidifies the cloud. This makes me think about how the medium of print may be able to change or undermine other aspects of a piece’s meaning. I must be careful as a printmaker to not have my medium undermine the work I create, i.e, digital print may undermine the foregrounding of the human touch and experience within my work, however the organic and natural qualities of etching may support it.

Secondly, Anthony Gormley’s beautiful ‘Untitled- King’s College Portfolio’ series. These pieces, to me, really echo his sculptural installation, ‘Time Horizon’ situated over 300 acres at the picturesque Houghton Hall in Norfolk. Gormley’s figures seem to occupy the same functionality as Constable or Friedrich’s small figures within their landscapes, allowing a lens from which to view the space, a pair of shoes that the observer can fill. These figures highlight the vastness, scale and imposition of the natural world. I am in love with the softness of these images that Gresham so expertly executes through screen.

Picasso- Printmaker Exhibition- The British Museum

This was perhaps one of my favourite exhibitions ever. Picasso’s amazing drawing and printmaking ability felt like a textbook on hand print technique. The subtlety and grace Picasso employs with his technique, especially his etchings, is marvellous. I especially loved his use of a sugarlift onto a greased plate, creating this really organic texture that is so expertly tamed into an incredibly detailed image.

‘Woman at the Window’- This was probably my favourite piece in the whole exhibition. It really demonstrated something that our Professor, Paul Coldwell, mentioned to us, about Picasso only using mediums that offer the least resistance, i.e, linocut but never woodcut. I’m not usually a massive fan of Lino-cut relief prints as I feel that they look a bit too ‘graphic design-ish’, however Picasso’s amazing eye for composition and light really makes this work shine for me. I love the object-source lighting created by the open window and I think that he really works with the strengths of the medium to create this amazing feel of reality in a very illustratorial piece of work. The simple colour palette also massively lets the fantastic lighting of this image shine. Throughout the course I feel that my tastes in artwork have massively changed, I still love the more detailed engravings of Doré and Durer, but something about these simple techniques that are executed with so much passion and subtlety feel somewhat more ‘true’ and evocative of the artist’s conceptual processes.

‘White Dove on Black Background’ and ‘The Hen’- These two pieces show an excellent subtlety of process and execute beautifully delicate painterly techniques on the plate. Both are examples of sugarlift and aquatint but in very opposing ways, with the ‘White Dove’ being a very contrast heavy piece, almost reminiscent of a detail from a Renaissance chiaroscuro scene, while ‘The Hen’ is a more traditional use of the technique. Both use stop-out varnish in really interesting ways, feeling almost like sgraffito marks, carved with a palette knife. I think that the subtleties of etching are so worth chasing, as you couldn’t develop this watercolour or ink drawn quality with these harsh oil-like scratches.

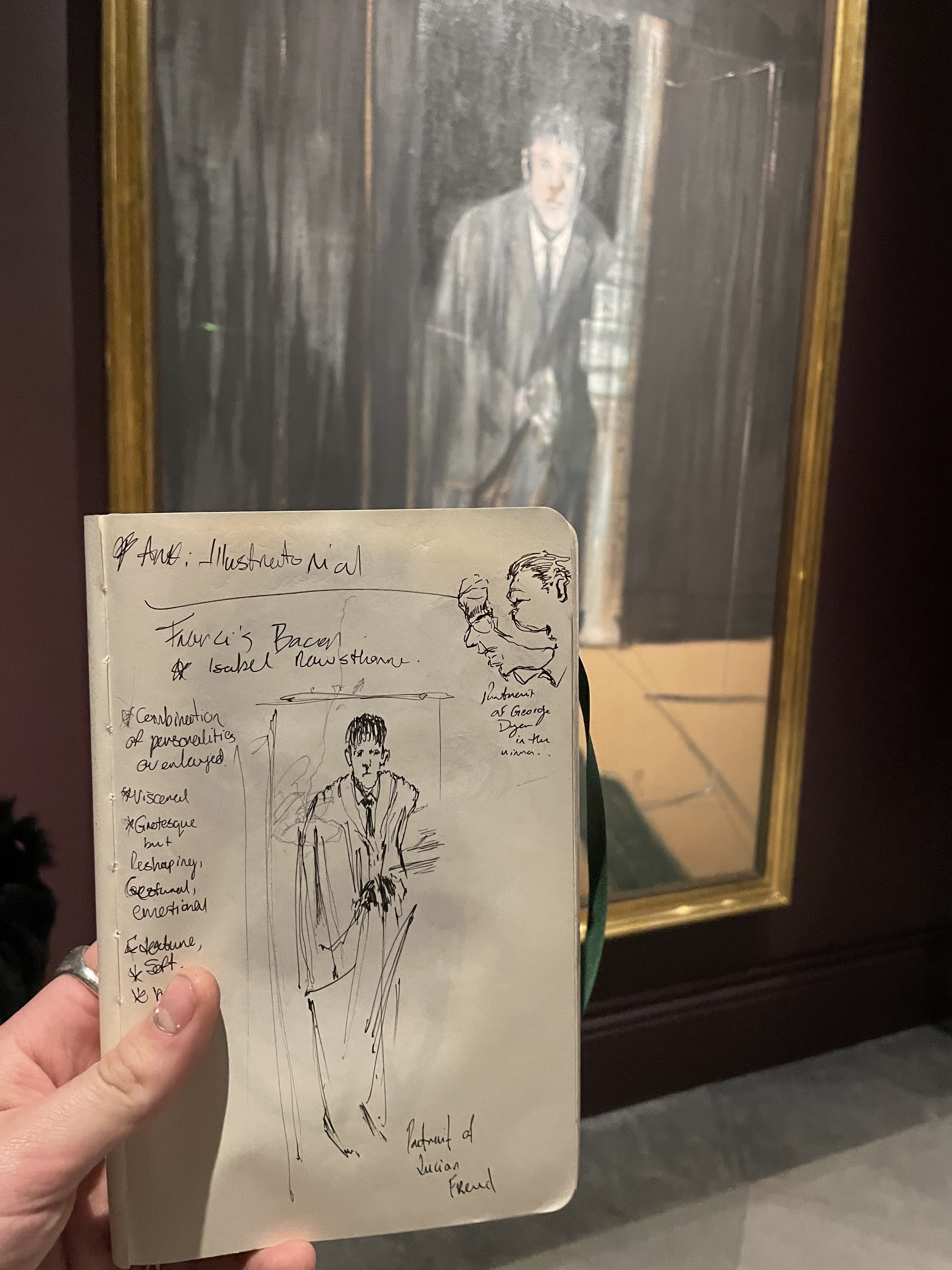

‘Human Presence’- Francis Bacon Exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery

This exhibition was fantastic, and although the subject matter isn’t massively related to my current body of work, I found this selection of Bacon’s work to be really inspiring. I had always had the assumption after seeing other pieces of Bacon’s work, such as his 1944 triptych, ‘Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion’, that the work was all immediately dark and terrifying. This exhibition, while definitely really unsettling, showed a more intimate and human side to Bacon, instead of viewing his uncanny portraits as scary, I began to see them as an understanding of his friends. Bacon would only paint people he knew very well, so as to capture the intricacies of their movements and tendencies in portrait, so instead we see this overlapping of personality, rather than mauled images of faces. There was an intimacy in these portraits that only someone who truly loved you could show, the ugliness and the reality of a person, presented as a holistic view of a relationship and a person’s beauty.

Healey Dell Research-

While I was home over Christmas, I was lucky enough to speak to the volunteers in charge of Whitworth Historical Society and Museum, they were kind enough to provide me with some very old images and postcards of the Dell. Due to the fact that the Dell is home to a very powerful set of waterfalls, the landscape is ever changing as the rock formations are slowly eaten away by erosion and time. I find it really interesting to draw from these old images as the old film stock does a great job at capturing ‘interferences’ from nature, such as hazy light plowing through the humid air, that modern cameras are too ‘true’ to capture.It’s also great to see this huge sense of deep history, comparing my modern photos to these and seeing the same views and places, but with a completely different appearance. It’s also really nice to see names I recognise, such as the caption in the photo on the bottom right, accredited to A. Lord, a relative of my friend Alex Lord. These images have provided an excellent base for me to draw from, with details from some of my large mono prints being taken from these images. When I go home again, I would like to interview some members of the society to try and glean some more folk knowledge and tales about the Dell. I like to inject my images with these folk stories, even if not visually apparent, I want my images to be ‘loaded’ with the divinity of nature and all of the ancient stories that lie behind these sacred spaces.

A Trip to North Norfolk-

My Nana was born in the seaside town of Wells-Next-The-Sea on the North Norfolk coast, her mother was born there, and her own grandmother was born a few miles away in the sacred village of Walsingham, home to the ruins of the famous Walsingham Abbey. After meeting my grandad as a policewoman in Manchester, she decided that she needed a way to keep returning to this place of beauty, and so they bought a tiny cottage in the nearby village of Stiffkey, affectionately known by it’s folk name, Stewkey, and I’ve visited there multiple times a year ever since. This deep history and connection to a place is a driving factor in my work and a lot of my early memories of summer holidays carving slides from the black tar-like mud of the creeks and watching the cacophanous skeins of geese threading through the sky with my late dad are some of the most poignant in my life. I spent some time on the marshes drawing and burying grounded plates in the mud and found this really exciting. There is a deep and cosmic secret lying in the ancient black marsh mud on the barren expanse of the Stiffkey salt marsh that gave the village its name. In the Domesday book, ordered by William the Conqueror in 1086, Stiffkey is recorded in Latin as ‘Stivecai’, or ‘The Island of the Stumps’, this name references the ancient fossilised woodland that rests silently beneath the sand and mud. There is something bone-chillingly fantastic about this to me, to be in the presence of these ancient natural constructs that have seen empires rise and fall is cosmic and terrifying, this insignificance of self is something that deifies these locations for me. The heavy and loaded silence that one might experience on entering a church is in these places, there is something deeply ancient and powerful here that is undeniable.

I was delighted to discover after a conversation with my great uncle, that in 1998, a couple of miles down the coast on Holme Beach, there was another ancient discovery, known as ‘Seahenge’1. The henge is a Bronze-Age timber circle, made up of a magnificent oak tree stump, upturned so the roots reach up to the heavens, surrounded by 55 smaller oak stumps. No one knows the true purpose of this fossilised wonder, but archaeologists have noted that this is one of the most significant Bronze-Age findings to date. There is much speculation on the original purpose of this ancient construct, but locals tell their own stories, saying that sacrifices to old pagan gods were laid in the mess of roots to have their innards pecked out by the marsh birds. Whatever the true purpose, it’s undeniable that there is some ancient power resting beneath the salt and sand in these places, and through my work, I want to show the power and sacredness of these locations.

The colourful history of this coastline doesn’t end there, Stiffkey specifically has its own host of folklore and old wives tales. The trees that protect the River Stiffkey are amongst some of the oldest oak trees in England, and the river itself was the vector for the holy stones that were used to assemble Walsingham Abbey around 1153, Walsingham itself has a whole host of religious history, with a vision of the Virgin Mary instructing its construction, and subsequently blessing a natural spring beneath the Abbey. The mysterious Black Shuck prowls the marshes of Stiffkey when the fog rolls in, an evil devil-dog with burning red eyes, and the ability to ‘wither’ people to dry piles of leather and bone. Finally, the whole submerged part of the North Norfolk coast was once known as Doggerland, and was above water, connecting England to the rest of Europe, who knows what secrets lie beneath the violent North Sea.

Exploring the Dell-

Healey Dell is probably the only thing my village has been known for throughout all of history, apart from a booming leather market that appeared somewhere between the 1950’s and 1980’s. In Drayton’s 1612 poem, Poly-Olbion, describing the different areas of Britain, he describes my home as “a dainty rill, which Spodden from her springs// A pretty rivulet, as her attendant, brings.”2, talking specifically of the River Spodden and its passage through the Dell. George Routledge sums up my opinions of Healey Dell as an ancient and sacred space, describing “A feeling a little less respectable than religious awe.”3. And John Roby, in his 1829 book, ‘The Traditions of Lancashire Vol.II’ talks of a harsh and awful winter in the Dell; “the dark and sterile aspect she displayed was bedizened with such beauteous frost-work, that light and glory rested upon all, and winter itself lost half its terrors.”4. Healey Dell has some really strange folklore based on one specific area that has always interested me, ‘The Faerie’s Chapel’, seen in the lower middle image above. The place feels uneasy, a large natural monolith protrudes above the violent white-water, known by two names, ‘The King Faerie’s Throne’ or my personal favourite, ‘The Coffin of the Faerie King’. According to Thomas Roby, and to locals, the strange formation of stone was created when the King of the Faeries aided Robert of Huntingdon, the current occupant of the ancient Healey Hall, to stop a curse that had been bestowed upon him by a local coven of witches. The King of the Faeries turned these witches to stone, creating the Faerie’s Chapel, which originally contained a pulpit and stone seats for unholy mass before being washed away by a flood in 1838. In return for his services, the King of the Faeries demanded Huntingdon’s Uncle’s ring, the only thing that proved his claim to his title as Huntingdon; this then set into motion the events that led Robert Huntingdon to become Robin Hood, the famous outlaw. Whether these stories hold any truth or not, it’s undeniable that the chapel is otherworldly.

John Tuck- ‘Landscape with a Distant Church’. Jack Cox- ‘View from Morston to Blakeney’

John Tuck is a fantastic watercolour and oil artist born in Wells-Next-The-Sea, he also happens to be the husband of my Nana’s late cousin, Mary. I’ve been lucky enough to chat to John Tuck a few times, although the conversations are quite one-sided! Tuck is a perfectionist and refused to sell my grandparents any work he didn’t deem gallery-level, even if they loved it. John is an expert at cultivating moody coastal scenes and his energetic brushwork, especially in his watercolours is second to none. I always find it fantastic visiting John’s studio, his garden is the most colourful and well-kept space I’ve probably ever seen, even at over 90 years of age, he still manages to upkeep it with a pair of secateurs and his zimmer-frame, yet on walking into his garden shed studio, I see a glimpse of the inner workings of his mind. Paint spattered on newspaper from decades ago litters the floor and open pots of solidified turpentine stain the air with the acrid scent of pine, the walls are crumbling away and it looks like his painting desk will collapse at any moment. I’m very lucky to be able to go and see John every now again, when he feels well enough to entertain me, and I find it really inspiring to see the work of a successful artist. I’d like to have a sprinkle of his genius rub off on my own work, as his beautiful compositions and muted colours are everything I aspire for my pieces to be. In the future, I’d like to interview John to gain some of his insight about his own fantastic landscapes and to reflect on why we both choose to make work from this spectacular place.

Jack Cox is another artist from Wells-Next-The-Sea, and a personal favourite landscape painter of mine. Cox also worked with oils and watercolour and painted the coastal views of the North Norfolk coast, especially the picturesque Wells Quay. Cox was a friend of my great grandfather, and in a couple of his paintings, including one on my grandparents wall, he can be seen working away at his boat, pipe in mouth. Me and my mum have always picked up on something we call a ‘Norfolk sky’ and Cox is probably the reason why we always come back to this. Cox chose to paint these gorgeous moody skies, that reflect back in the glassy stillness of the Quay that could only be captured by his insistence in painting en plain air. A lot of the skies I’ve chosen to create in my landscapes are in direct reference to Cox’s work.

It’s important to me to study the works of these artists that are so close to home, as they are one, depicting the same scenes as I want to depict, but two, are also historically connected to me in one way or another. I’ve always been very insistent that art is so fantastic to me because just by creating work you are instantly connected to an ages-old human practice of making. This is one of the reasons I love etching, due to the fact that the same processes and tools have been used in the same way by other makers for hundreds of years before me. But something about finding kindred artists, that have a real concrete connection to me, as well as a passion for creating the same things, depicting the same subjects is really exciting and grounding in my practice.

[1] The British Museum. (n.d.). The art of Seahenge. [online] Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/art-seahenge. (Accessed 15.01.25)

[2] Drayton, M. (1612, Canto. 27, P.129). Poly-Olbion.

[3] Routledge, G. London. (1844, p.168) The Pictorial History of the County of Lancaster

[4] Roby, J. (1928, p.6). Traditions of Lancashire Vol.II.